There is no doubt about it. The Southeastern Ceremonial Mound Culture originated near Lake Okeechobee, Florida, in Ocmulgee Bottoms, Georgia and the Nacoochee Valley of Georgia . . . long before the construction of mounds at Cahokia, Illinois. It was a direct result of Itza and Chontal Maya Commoners emigrating to Southeastern North America in large numbers and mixing with earlier Panoan mound builders, who arrived around 1-200 AD from eastern Peru and Uchee mound-builders from across the Atlantic, who arrived much earlier. Mexican anthropologists have always wondered what happened to the Itzas, when a massive volcano eruption depopulated Chiapas.

In the Nacoochee Valley of Georgia, archaeologist Robert Wauchope discovered a continuous upward cultural evolution from around 1200 BC to a catastrophic smallpox epidemic in 1696, in which each wave of immigrants added to the sophistication of the densely packed villages. In other words, the Itza immigrants blended with the peoples, who came before them and after them.

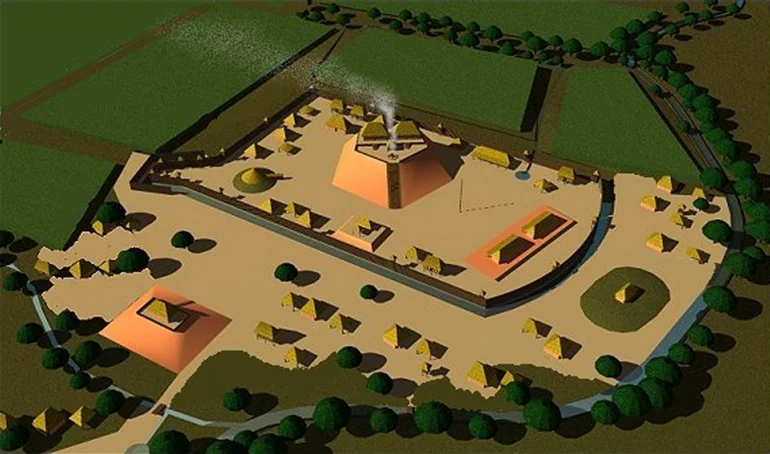

Image Above: This architectural rendering portrays a typical Proto-Creek temple that sat atop either a mound or a terrace complex. They were stuccoed with a mixture of fine clay and mica chips, which made them glisten like they were sheaved with gold. In actuality, they were quite similar to the Maya temples constructed before the 600s AD. Temples in smaller or poorer towns probably always had thatched roofs. Painted Buntings were considered sacred by the Apalachete and Itzate Creeks. The lived in the roof lofts of temples. Eyewitness accounts state that the Apalachete and Itzate Creek priests burned copal incense 24/7 at the temple. This was true for Maya temples also.

Construction of the major agricultural terrace complexes in northern Georgia probably began in the early 800s AD. The eruption of the El Chichon Super-volcano in 800 AD had forced surviving Itza terrace farmers to flee for their lives. At this time, the land in the Yucatan Peninsula was crowded and the economies of most Maya city states were collapsing due to chronic warfare and excess building. Initially, the farmers used logs cut down at the terrace site. After about two centuries, there were no more logs in close vicinity, so they began piling stones to support terraces.

Before discussing the origins and history of the Itza People in Mesoamerica in Part 63, we will look at the profound evidence . . . even the Creek migration legends . . . that there were four waves of Maya Commoner refugees, which settled in Southeastern North America. The approximate dates of these migrations were (1) c. 538-600 AD, when multiple volcanic eruptions in Central America, Iceland and Indonesia cause a collapse of Teotihuacan and temporary collapse of Maya Civilization. (2) 800 AD, when the eruption of the El Chichon super-volcano incinerated much of Chiapas (3) c. 990 AD, when Toltec invaders emptied the suburbs of Chichen Itza and (4) 1200-1250 AD, when Nahua invaders caused many tribes to abandon Tamaulipas, southern Veracruz and Tabasco.

Prologue

In May 2015, when reading the contents of a wooden box at Lambeth Palace, England . . . originally dispatched by Georgia Colonial Secretary Thomas Christie on July 7, 1735 to King George II and Archbishop of Canterbury . . . I was surprised that it contained much more than the original manuscripts of the so-called “Migration Legend of the Creek People” from June 6, 1735. That document was really the migration legend of one town, within one tribe that was one of the members of the Upper Creek Division of the Creek Confederacy. They originated on the slopes of the massive Orizaba Volcano in southwestern Veracruz. Most of the other branches of the Creek Confederacy originated in some part of eastern or southern Mexico. The major exceptions were the Highland Apalache, Chiska, Konasee and Shipape, who came from Peru, the Savano, who were indigenous Algonquins and the Uchee, who said that they originated in Europe.

While Muskogee Creeks in Oklahoma claim this legend as their own, there is currently no known migration legend for the Muskogee-speaking Creeks. Mid-17th French natural scientist, Charles de Rochefort called the Muskogee-speakers Kofitachete (Mixed Race People) and placed their homeland in the mountainous region of North Carolina, south of Asheville, east of Franklin and around Hendersonville, Brevard, Highlands and Sapphire Valley, NC. Their branches included the Koweta, Culasi, Curahee, Tokee/Tokasi, Tokabatchee and Oakfuskee. Muskogee contains many Gaelic, Proto-Scandinavian and Latin root words, which are missing from Itsate Creek, Chickasaw and Koasati. Yes, Kofitachete means the same as the town visited by Hernando de Soto in South Carolina, Cofitachequi!

There were several other migration legends within the box, for other linguistic divisions of the Creek Confederacy, plus the statement that the most recent Creek Confederacy was not founded until 1717 and that the Chickasaw tribe was one of the founding members. The previous confederacy, known as the Kingdom of Apalache or Apalachen Confederacy, had stretched from southwestern Virginia to Eufaula, Alabama. It had collapsed after the catastrophic smallpox epidemic in 1696.

The non-Muskogean Cherokees had been vassals of the large Tamahiti-Creek town of Katalu in SW Virginia and the Apeke-Creek town of Chakata in NE Tennessee . . . and therefore, were members of the Apalachen Confederacy until they betrayed their comrades in December 1715 at the Uchee village of Tugaloo. The Cherokees murdered the other 32 leaders in their sleep, thus precipitating the 40 year long, Creek-Cherokee War. At this point, Katalu moved the Chattahoochee River in what is now North Metro Atlanta. Chakata moved to what would become Talledega, Alabama.

I quickly realized that much that one reads in online references about the earliest days of Savannah, GA and the Creek leader, Tamachichi (Tomochichi in English) was inaccurate. None of the anthropologists and academicians in Georgia seem to know that Tamachichi means “Trade Dog” (itinerant trader) in Itza Maya.

Here is what he told Edward Oglethorpe on February 12, 1733, while the two were strolling about the site of the future site of the City of Savannah: The ancestors of Tamachichi had sailed northward from Mexico over the Great Water and first lived by a large lake in southern Florida. They next moved to a region with shallow water and vast expanses of reeds. This could be the Everglades, the headwaters of the St. Johns River in Florida, Lake Serape (now Okefenokee Swamp) in Georgia or the famous tidal marshes of the Georgia Coast. They next moved to a large town, where Savannah is now. Their final move was to the Ocmulgee River Bottoms at Macon, GA. This would be the founding of Itzasi (the Lamar Village) around 990 AD.

Until 1717, Tamachichi had been High King of an alliance of towns and villages along the Ocmulgee River. He was banished from the territory of the Confederacy because he had ordered the massacre of a fortified trading post on the plaza of the Ocmulgee mounds in 1715. This was the time of the Yamasee Uprising.

He wandered around the periphery of the new Creek Confederacy’s boundaries for many years, earning money as an itinerant trader before being allowed to settle in or near Parachikora (Palachicola) on the Savannah River about 37 miles upstream from its mouth on the Atlantic Ocean. There he worked as a slave catcher . . . catching both Native American and African slaves as they attempted to cross the Savannah River in order to reach the sanctuary of the Spanish Province of La Florida, south of the May River (now called the Altamaha River).

In 1731 or 1732, Tamachichi learned that a new colony was being founded, which would occupy the portion of South Carolina between the Savannah and May (Amicalola) River. It was the former site of a large town, which had been abandoned in the 1600s. Currently, there were no occupants and that part of Georgia was not part of the Creek Confederacy territory. He gathered together about 50 followers and settled a village on Yamacraw Bluff a few months before the settlers were to arrive. Despite what Wikipedia tells you, there was no province of “Yamacraw” Indians in that part of the future state of Georgia. Tamachichi was, at least initially, a con artist. He sold land to the Georgia Trustees that he didn’t really own.

Palachicora had formerly been the fortified town of the elite on Irene Island, now part of the harbor facilities of the Port of Savannah. Its name is recorded at Chicora in the Spanish Colonial Archives and Chiquola by the records of the French. In his memoirs, French Captain René de Laudonnière. Commander of Fort Caroline, specifically stated that Chicora and Chiquola were the same town and located 8 French leagues (18 miles) up the Savannah River. By 2015, I knew that all European maps called the Altamaha River the May River until 1722 and placed Fort Caroline about 11 miles inland on the south side of the Altamaha River. Tamachichi added that the Creek and Uchee communities, living in the Savannah River Basin, still remembered the time that a red-haired Frenchman (Captain Jean Ribault) sailed a bark up the Savannah River and met with the leaders of Palachicora. That was in 1562 AD.

The commoners lived in the village of Yamacora (Yamacraw in English archives) which is now Downtown Savannah. There would continue to be a small village of Creek and Uchee Indians living next to Savannah until the outbreak of the American Revolution. Tamachichi showed James Oglethorpe the three mounds overlooking the Savannah River, where his ancestors were buried.

Itzate – Kenimer Mound

The Kenimer Mound, near where I live now, is the oldest example of Itza style architecture in the United States. The Itzas and their close kin, the Kek-chi Mayas, traditionally sculpted large pentagonal earthen pyramids from hills to use as platforms for their Sun God temples. The State of Georgia, plus the highlands of Chiapas and Belize, are the only regions in the world containing numerous five-sided earthen pyramids.

The Kenimer Mound probably dates from around 600 AD. In 1999, after signing an affidavit for the property owner, promising not to do any excavations in the mound site, a team of archaeologists from the University of Georgia went ahead and excavated test pits anyway. They found a preponderance of Napier type potsherds. Napier style pottery appeared in North Georgia around 600 AD.

The other Itza sites

Tamachichi’s ancestral band of Itza Mayas from southern Florida, who settled on the Ocmulgee River around 1200 AD, joined other Itzas, who had established a village two miles south of the Ocmulgee Acropolis around 990 AD. A few years later, they established a large town on the Etowah River, which became Etowah Mounds . . . a village on the headwaters of the Chattahoochee River, which became Itzate and the Nacoochee Mound . . . a village on the headwaters of the Little Tennessee River in Northeast Georgia (which became the Dillard Mound). Itza Commoner refugees poured into the Southeastern United States during that period with their shell-tempered redware pottery, thus triggering the sudden appearance of “the Mississippian Culture.” The region between the higher Blue Ridge Mountains in Georgia and the Smoky Mountains in Tennessee became known as Itzapa . . . Place of the Itza or Itzate Itza People).

Okate, Okute or Okani: The ethnic name means “Water People” in South Florida Itza. They seem to have originally been the same people as Tamachichi’s ancestors. They migrated to South Florida around 800 AD, but eventually moved to Lake Serape (Okefenokee Swamp). Serape is a Panoan word from Peru, which means that the bank of a lake or stream is crumbling into the water. Around 1150 AD, at the same time that construction ceased on the acropolis at Ocmulgee, most of the Okate immigrated to the Oconee River Basin of Northeast Georgia. Here they constructed small, fortified towns for the elite as they established political dominance over the dispersed Uchee farmsteads in the region. Eventually, they established a large colony on the Oconalufte River at the foot of the Smoky Mountains.

Itzate-Eastwood Village: Archaeologist Robert Wauchope never knew of the Kenimer Mound’s existence, but he did excavate the Eastwood Village, immediately west of Kenimer Hill. It contained the oldest known examples of Chickasaw architecture and town planning traditions. It probably also dates from around 600 AD. Chickasaw houses were shaped just like the oval Maya houses in eastern Campeche, but were fabricated from saplings, wattle and daub.

What appears to have been the situation is that a relatively small band of Itza Mayas established a market town to extract gold and mica from the Nacoochee Valley around 600 AD. The commodities would have been shipped by canoe down the Chattahoochee River to the Gulf of Mexico. By this time, proto-Chickasaws had established villages as far east as northwestern South Carolina at the Simpson Field Site in Anderson County, SC. Those proto-Chickasaw, who settled near the Itza Maya elite absorbed some of the Itza cultural traditions, agricultural practices and vocabulary. For example, the Itza word for trade, tama, became the Chickasaw word for maize.

The Nacoochee Valley Chickasaw became the seed population, which evolved into today’s Chickasaw cultural and architectural traditions. Chickasaws continued to live south of what is now called Yonah Mountain until 1817. Even after their land was ceded by the Creek Confederacy, many Chickasaws elected to assimilate into the mainstream population of Georgia, rather than move to either Alabama or Oklahoma.

Footnote: According to the earliest precise Georgia state maps, Noccosee (Bear) was the original name of Yonah Mountain during Native American occupation and the name of Chickasaw village, near where Cleveland, GA is today. The Chickasaws and Creeks ceded their last holdings in Northeast Georgia in 1817.

Itzate-stone box sarcophagi – Nacoochee Mound

Both the Maya and Creek commoners typically buried their loved ones under the floor of a house or immediately next to it. Ana the Campeche Tour Guide With Benefits taught me something very useful to our current research projects. The Itzas, plus several other Maya tribes in the Yucatan peninsula buried their dead in stone-lined sarcophagi . . . either under the floor of the house or adjacent to the house. Human remains were quickly dissolved by acidic tropical soils, but one could find old village sites by looking for rectangular arrangements of field stones.

In 1915, amateur archaeologist, George Gustav Heye, excavated the entire Nacoochee Mound. He found that the mound originated as a cluster of stone box sarcophagi, dug below the original soil surface. Additional soil was dumped over these burials, then more stone box graves were constructed. At some point in the past, which Heye was not able to discern, the Creek’s ancestors switched to just burying their dead in the soil.

Stone box sarcophagi are also endemic in the Nacoochee Valley, perhaps even more densely deposited than typical Pre-Columbian Maya village sites, where the soil is far less fertile. By 1939, when archaeologist Robert Wauchope was excavating stone box sarcophagi in the Nacoochee Valley, he was already an expert on the houses of Maya Commoners. He even noted the similarity of the practice by the Creek’s ancestors of placing stone box graves near or under houses to the Maya custom. He also recognized that many male skeletons in the Nacoochee Valley had flattened foreheads like those of Maya males. However, it never dawned on him that they were the same people. Like most North American archaeologists, then and now, he knew very little about the languages spoken by the Mayas and the Creeks. If had known that where he was working was called Itsate and Itsate means “Itza People,” he might have interpreted his findings differently.

The Tamahiti of Virginia

During the summer of 1992, when the presence of Vivi the French Courtesan on my Shenandoah Valley farm, made every day heavenly, one of my projects was the restoration of a late 18th century house, which would become the rural escape for political consultants, James Carville and Mary Matalin. They were planning to marry in 1993. While excavating the septic tank field, the front end loader was constantly being hung up by stone boxes containing ancient skeletons, painted Mesoamerican type pottery and stone Mesoamerican style metates.

I remembered seeing the stone box sarcophagi in Yucatan, but also knew that all human remains had to be reported. The county coroner begged me not to fill out a report as required by Virginia law, because he said that the stone box burials were endemic in the county and had always been a nuisance for farmers.

I called the Department of Anthropology at the University of Virginia to ask a professor to investigate some ancient burials, since they were identical to those of Maya Commoners in Mexico. The secretary tried to get a professor passing by her desk to talk to me, but once she said “Maya Commoners and Mexico” he refused to do so and laughed me off the phone.

Twenty years later, I stumbled upon A History of the Valley of Virginia (1830) by Sam Kercheval. Kercheval specifically stated that there were originally hundreds of mounds in the Shenandoah Valley, plus that stone box graves and Mesoamerican style artifacts were endemic in the bottomlands of the Shenandoah Valley. He clearly stated that these previous occupants of the Shenandoah Valley were American Indians from Mexico and that they were wiped out in the 1670s by Native American slave raiders from further south. He speculated that the Tomahitans were the survivors of this massacre. They lived in southwestern Virginia until 1716, when they returned to their homeland in Georgia, due to the outbreak of the Creek-Cherokee War. Tomohitan is the Anglicization of Tamahiti, which is a pure Itza word meaning, “trader or merchant.” Tamahiten is the plural form of the word.

Chiaha in Western North Carolina

Chiaha is a pure Itza word that means “Salvia – River.” This makes sense because the chroniclers of the De Soto expedition mentioned that the broad river bottomlands in the Chiaha Province were filed with salvia fields. The Itza Mayas were always known for growing salvia (chia seeds) on a large scale. Chiapas means “Salvia-place of.” When Spanish chroniclers used the term, Ichiaha, they were refering to the province’s capital. Both in Itza and Eastern Creek grammar, an I or E in front of a proper noun means that it is the principal one of that ethnic group or the capital.

The De Soto Chroniclers mentioned one other observation that is strong evidence that Itzas settled in the North Carolina Mountains. They said that the people of Chiaha kept stingless honey bees in their homes, which provided honey and pollenated the salvia fields. The Mayas developed a stingless honey bee, which they still keep as pets in their homes. It is the only domesticated, indigenous honey bee in the Americas.

The Stone Box Grave People of Tennessee

Around 1050 AD, a culturally advanced indigenous people occupied the Cumberland and Duck River Basins of north central Tennessee. Although stone box sarcophagi can be found throughout the State of Tennessee and surrounding regions, they are particularly abundant in the Nashville Metropolitan Area. Thousands of such burials have been found here. Their builders were also skilled ceramic artists, whose work appears suddenly on the archaeological record. Like the Stone Box Grave People in northern Georgia and northwestern Virginia . . . and the Mayas in Mesoamerica, the men had flattened foreheads that were created by binding babies’ heads. This culture disappeared from the Nashville prior to the arrival of European settlers in Tennessee. The land around Nashville, southward, was claimed by the Upper Creek Indians until the early 1800s.

Late 19th century and most 20th century archaeologists from such institutions such as the Smithsonian Institute assumed that the Stone Box Grave People came from the Middle Mississippi River Basin, often specifically, Cahokia, Illinois, since it is north of the Mason-Dixon Line. However, most of the mounds at Ocmulgee in Georgia were begun 150 years before mound construction began at Cahokia, so it was obviously not the Mother Town of the Southeastern Ceremonial Mound Culture.

In Part 63, we will examine the history of the Itza Mayas in Mesoamerica. Originally, they were immigrants from South America, who did not speak a Maya dialect. Their priests continued to use this mother tongue for centuries, instead of Maya, during rituals and to conceal their discussions from potential enemies.